Any photographer who considers themselves to be a creative or an artist, is usually delighted when they are ask to photograph for a corporate client, and then almost certainly frustrated by the constraints. So why can’t corporate photography be art and be recognised for the quality and power of the image?

This is front of mind for me at the moment because a series of, what I think are really strong environmental portraits, have to be removed from a booklet before it is even printed because the client has embarked on a restructure, which means a number of those photographed are no longer employees.

Add to this the usual demands to photograph within brand guidelines, which these days often seems to mean veering towards over-exposure and lens flare, and the work of the photographer is reduced to technical expertise.

Why is it that the majority of businesses do not recognise when their photographer is doing great photography irrespective of whether it conforms to brand guidelines?

Corporate Art

In a Bloomberg article titled ‘Banks are the New Medici when it comes to art collecting’, the author explains how banks around the world are amassing a vast collection of artworks for their offices. Of course, the same is true for businesses in other sectors as well, making ‘corporate art’ one of the most important outlets for today’s artists.

‘The way we have approached collecting has been anchored in living artists’ The curator for Royal Bank of Canada was quoted as saying. UBS and other banks also made the same claim; they weren’t buying expensive art from auction house, instead they were the modern day patrons of living artists.

Fine art, sculpture and photography are all being purchased by businesses, but why?

Cultural Responsibility

In his book, Corporate Cultural Responsibility, Michael Bzdak argues ‘..corporations have a great deal of value to contribute to the well-being of society by supporting and sustaining the arts…’ He continues ‘…companies that engage with their stakeholders around the arts, design and culture will be rewarded in both tangible and intangible ways.’

This was understood by Victorian industrialists in Britain who built theatres, galleries and subsidised access to cultural events as a pillar of corporate culture and employee loyalty.

Port Sunlight is a village set in 130 acres that was created by William Hesketh Lever in 1888 for the employees at his soap factory. Not only did Lever pay particular attention to the architecture, he also incorporated an art gallery that is still open today. There are other examples in the UK, such as Saltaire village built by Sir Titus Salt, and Bourneville created by Cadbury. Later generations focussed less on housing and more on the arts and access to cultural activities such as John Spedan Lewis of the John Lewis Partnership. This desire to support and provide access to the arts was happening all over the world, Carlsberg, Pirelli, Rockefeller, Carnegie and more. It seems clear that since the 1800s, capitalism and the arts have been good bedfellows.

Art vs Commercial Photography

When it comes to photography, businesses regularly employ photographers to document the work that the business does but very few commission original work for display. I wonder why?

Last year I read of a London restaurant owner who commissioned a number of street photographers to capture images around the vicinity of the restaurant to help create the atmosphere he wanted diners to experience. Independent hotels have been known to the same thing.

In most instances businesses will purchase rather than commission. Currently on exhibition at the UBS Art Gallery in New York is a collection called ‘Reimagining: New Perspectives’ and included are at least four photographs from contemporary photographers.

Deutsche Bank’s offices around the world are home to hundreds of the 57,000 works of art it owns, which includes work from photographers including, Carrie Mae Weems, Xavier Simmons, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Zhu Jia, Olaf Nicolai, Thabiso Sekgala, Papa Hristova.

More of Deutsche Bank’s art is currently at the Palais Populaire in Berlin with an exhibition titled ‘The Struggle of Memory’, which has many photographs included.

Why can’t corporate photography be art?

Many organisations document their journey as an entity. New people, new technologies, new buildings, new markets, social impact, and charitable contributions are all stories that are captured so that existing stakeholders can celebrate; and future stakeholders can reflect and map the life of the organisation.

Today, these images are often kept in digital form on servers, often times fragmented and unlabelled, too distant from the moment of capture to accurately annotate. Larger collections are curated and kept in archives, available to employees and researchers with an interest in corporate history.

Is there a point in which this type of business photography is also art?

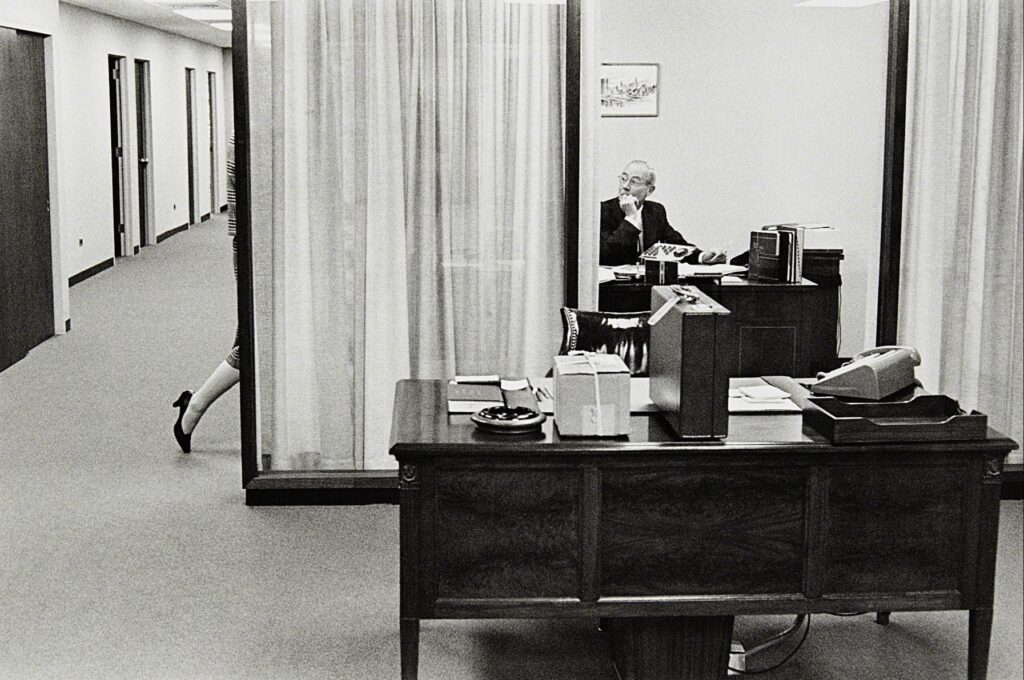

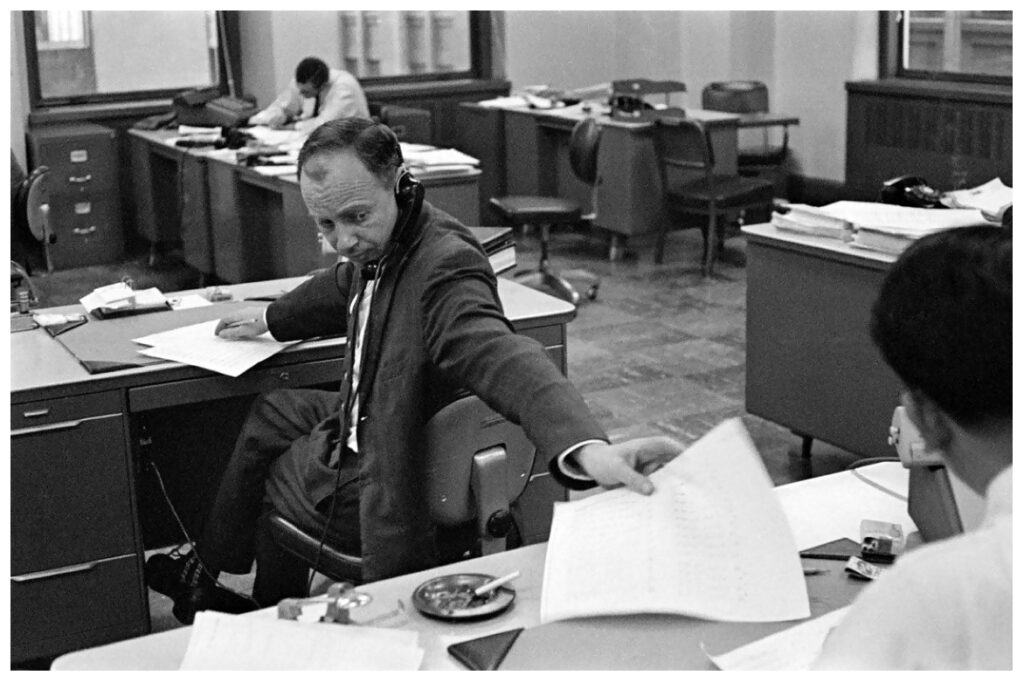

In 1960 Bank of America commissioned the photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson to photograph for it annual report and accounts. A print of one of those photographs, ‘Bank Officer and His Secretary’, sold at auction in 2018 for $6,250. It is a great photograph. It is art but it was commissioned for a report, and I doubt anyone told Cartier-Bresson to follow brand guidelines.

How much of the work currently being commissioned by businesses around the world could also claim to be art? How much is worthy of hanging in the foyer for its own artistic value, whether the people featured are employees or not?

This starts with the person commissioning the work. Do they want art? Or do they want an image that conforms to brand guidelines, which these days extend to the use of the photography. I’ve seen guidelines where high contrast, bokeh and depth of field are dictated by the marketing team, and I’ve also been lucky enough to be told to create what I think looks good without having to worry about branding, but this is increasingly rare.

I think it would be more refreshing for those commissioning work to look at the style of the photographer and then allow them to freedom to interpret the brief in their style. This happens in entertainment and fashion, a prime example being Greg Williams, who is employed because he captures candid images in black and white that have a ‘caught in the moment’ feel about them. This is what he is famous for and why people employ him – not because he’s a photographer, but because his photographs have a particular signature style.